I really enjoyed reading the debates around choosing boring or exciting technology. In my opinion, there is another interesting point, beyond new or old, that is about longevity, or durability.

Some software can be deliberately ephemeral, like a mobile app for a specific event. But usually we want software to last as long as possible, like a Web API with millions of clients.

As I outlined in a previous post, long term maintenance takes all sorts of efforts. And logically, applications with the least maintenance cost are more likely to last longer.

So, what makes software durable? How can we take long term maintenance into consideration during the design phase?

tl;dr: Think of your software architecture as a multi-generational building. Simplicity and adaptability are key to guarantee long term survival in a constantly changing environment. Designing for the long term requires experience and judgement, so focus on values and people more than technologies.

Typical Lifecycle

From my experience, the typical phases of software engineering are:

- Define the needs and requirements

- Assemble a team

- Design, develop and deploy

- Validate conformity

- Dismantle the team

- Run and maintain forever

The last phase is the critical one: you go from a top priority project, backed by a whole team with daily activities, to a low priority project, with a few people involved only sporadically. And it can last years.

What if we would build software with this critical last phase in mind?

Engineering is 99% managing legacy, 1% deciding on what legacy you want to have in the future. ─ @rakyll, 20 sept. 2021

Elegance vs. Adaptability

A CTO recently reminded his teams [1] that they should «build boxes, not arches». He uses this metaphor to remind programmers that elegance in their design should not delay the production of value. Arches are more elegant than blocks, but they show value only when the top key stone is put. Unlike arches, blocks can be easily rearranged and replaced over time, helping adaptability and market fit.

I could reuse this metaphor, and say that blocks are more likely to last over time than arches.

In the book How buildings learn, Stewart Brand shows that buildings which were built quickly to look impressive have a terrible maintenance record.

Engineers who want exciting technology in their curriculum are like architects who want beautiful buildings in their portfolio. Do they really care how practical it will be over the years? Is it built to last or to shine?

Notre-Dame Cathedral reconstruction © habibeh Madjdabadi architecture Studio

As Joel famously wrote 21 years ago, «rewriting the code from scratch is the single worst strategic mistake that any software company can make»: [2]

Programmers are, in their hearts, architects, and the first thing they want to do when they get to a site is to bulldoze the place flat and build something grand.

Do we want to build, demolish, and rebuild? Or should we design software like a building where engineers and operators have to live for several generations?

When aiming for eternal design, you must focus on an architecture where it is viable to «fail fast, fail small, fail often, learn, and reiterate».

Pace-layered Design

How do you balance stability and adaptability with innovation?

I would advise you to spend 30' to watch how buildings are built for change. The parallel with software is very inspiring. You'll think of your application code as a structure with solid, simple, slow-moving foundations, whose upper blocks can be replaced and remodeled, fostering innovation. You want to be able to repaint bedrooms or replace windows without jeopardizing life in it!

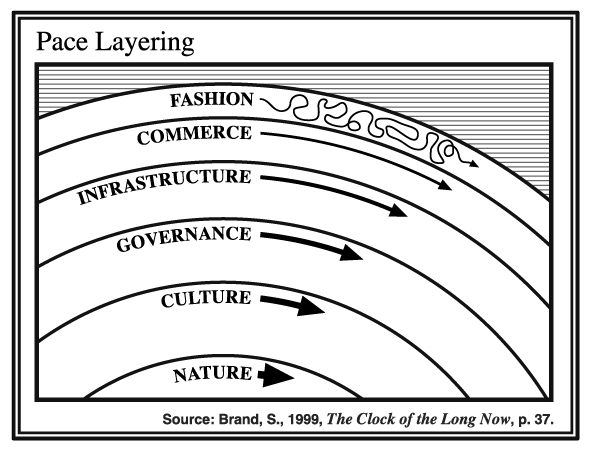

Everlasting, slow, and powerful core layers, versus ephemeral, fast, and weak skin layers

The firm Gartner applied this concept of shearing layers to software, where each application layer obeys to a different strategy:

- Powerful lower parts move at slow pace: Change is risky and expensive, strict and only incremental (APIs, databases, ...)

- Middle parts adapt to business: Change occurs more often, following the company's business processes and specifities (custom integrations, SaaS, cloud...)

- Top parts move fast: Change requires less governance and planning, encouraging experimentation (proof-of-concepts, frontend, ...)

Uncle Bob's also advocates the same ideas in his book about Clean Architecture. Breaking the myth that restarting from scratch is a solution, he expands familiar principles like SOLID and SoC to system architecture.

Wear and Tear Parts

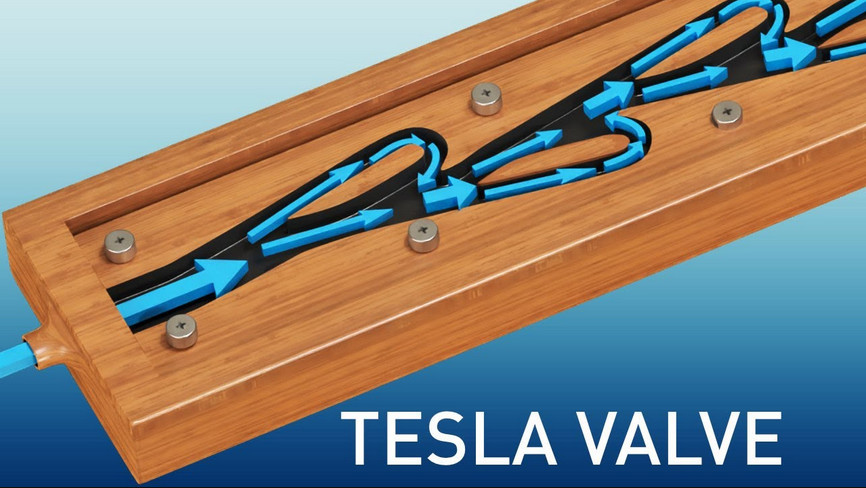

Compare a classic reflux valve with the valve designed by Nikola Tesla. One has at least two moving parts, a spring and a «stopper», the other one has none, which gives it an almost infinite lifetime.

When your application handles a request, what moving parts are involved?

Compare the moving parts of a statically generated website, with one powered by Wordpress, relying on a MySQL database, a Web server running PHP, with extensions and system libraries, an Admin UI in React, a Varnish cache... With the former, you write your articles in Markdown, run a command once to generate the HTML pages, and simply serve the static content to millions of readers, without any moving part. No monitoring, no security patches, and resilient to system upgrades. In twenty years, even if the script that generates the files doesn't run anymore, the website will still be online.

Take MDN for example. It used to be powered by a Django application with thousands lines of code. Instead of this complex wiki application, the team replaced it with Markdown files in a Github repo, and some commands to publish the HTML website.

Similarly, Tim showed us how they fixed the BBC News app scaling issues by prerendering content into static files on Amazon S3, instead of relying directly on BBC Web services.

It's not all or nothing, just make sure to think about how much resources, machines and people, will be required to operate this service years after the original team built it.

Conviviality

In 1973, Ivan Illich wrote Tools for Conviviality. This book contains radical ideas about progress, emancipation, and technology. Illich explains how it is crucial to be able to share, understand, repair, and modify our tools in order to reach independence over the long term. It is not a coincidence if the book had an immense influence of the first computer hackers [3].

Which of the appliances that you own are repairable?

The iFixit Manifesto says it clearly: «If you can't fix it, you don't own it».

Not so long ago, if your Citroën 2CV's belt broke in the middle of nowhere, you could use your nylon stockings as a temporary spare part and make it home.

One of the old cars of my colleague Florian, long term Gecko hacker :)

If you build your whole application (or business!) on the unique features of a cloud solution (Spanner, Firebase, ...) or on the latest trendy all-in-one framework, you obtain the opposite of conviviality! Avoid vendor lock-in! You will need to use their specific screwdrivers to repair it, you won't find standard spare parts, and years later planned obsolescence will threaten you. Avoid «easy» (no effort), and go for «simple» (no complexity).

Simple is understandable. Simple scales. Simple always wins over the long term. Think more like ARM, and less like Intel :)

Beware of Over-engineering

Most intelligent people produce intelligent designs. The reality is that their creations eventually become extremely fragile, costly to maintain, or they just don't survive the company's successive turnovers. Because most of us aren't super smart, are sometimes sleepy, often very lazy, or with scars from the past.

I recently fell upon this example, where a piece of JavaScript will produce a static Dockerfile. What's wrong with static files? It's not because you can do it, that you have to do it!

Discriminating intelligence is crucial.

In the past, we would build Web services as big monoliths. Microservices emerged in early 2010s, mainly as a response to the needs of continuous deployment, following the Unix philosophy. After a decade of hype, where engineers would build all sort of applications using dozens of tiny services, in the late 2010s, monolithic applications became acceptable again. And as people with discerning abilities sensed it early, you should just «start with a monolithic approach and move to microservices if needed».

Skin in the Game

Like factories and towns who release their waste in the river, assuming others downstream will handle it, some engineers and managers consider themselves as builders, and will let future fixers handle maintenance over time.

Taleb explores this mistake in his book about Antifragility:

Every captain goes down with every ship

If a engineer (or a manager) collects benefits when she/he is right and let others pay the price when she/he is wrong, the result will be fragile.

Like UX designers who don't use their app, or architects who don't spend time in their buildings, software developers who never have experienced the romance of maintenance are less likely to produce long lasting solutions.

Engineers should experience being maintainers.

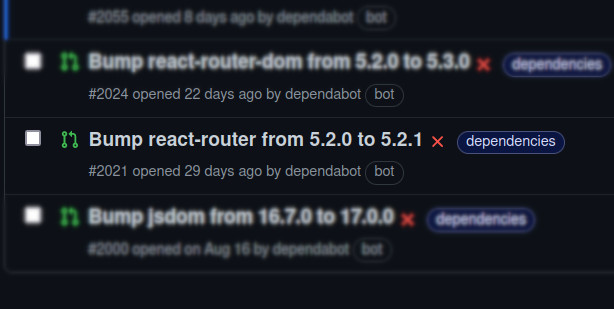

A patch version upgrade of React Router breaking the entire app.

You need first-hand experience, having done mistakes, and having paid the consequences, or your ships will keep drowning.

Experience helps you adjust priorities in life. You grow up. Age doesn't really matter. You may have missed the joy of upgrading Redmine on your personal server 15 years ago, if you had to deal with upgrades of React Router in your SPA recently, you know what this is all about. You paid the price of your bad draw. You now have less patience to deal with fragile stuff. You aim to work less, and that's extremely beneficial when it comes to designing solid and durable stuff.

I think that it's also one of the succesful ideas behind Dev Ops, when developers are also accoutable for running their stuff in production.

Technology Pick

Which technology will stand the test of time?

I like one of the first answers to this tweet, arguing that «paper didn't change much, that's why!». In the world of software, and technology in general, the environment evolves constantly. Some top-notch innovations of yesterday become mainstream building blocks of tomorrow. Others fall under the pressure of the heartless natural selection of their ecosystems.

There are rational criteria to maximize your chances, but life always remains full of surprises :) Naturally, technologies capable of embracing and coexisting nicely with other ones have a better chance to survive! Rust, for example, can be executed from almost any language, from Python to Javascript, and can itself execute external libraries written in C++, which makes it a great tool for gradual rewrites.

We can argue that you should listen to your old guard. They've seen trends pass by, their sweat shirt may not be cool anymore, but they've washed it a thousand times and it still does the job nicely. They have a lot less free time than young intrepid engineers, and are therefore less likely to reinvent the wheel.

Successful technologies with a low rate of evolution can be a good bet. As Nico said, a Gibson Les Paul doesn't need any enhancement, it's simple, built with quality, and maintenance will only consist in replacing the strings from time to time. That's also one of the reasons why I enjoyed working with Pyramid, instead of Django.

The Lindy effect gives an interesting perspective too: the future life expectancy of some non-perishable things, like a technology or an idea, is proportional to their current age. Obviously, other forces like the network effects come into play. Do you realize that the usage of jQuery only started to decline at the end of 2020?

Besides, you cannot ignore recruiting. Perl enthusiasts can argue that their ecosystem is fantastic because any library upgrade is almost guaranteed to be backward compatible, nonetheless it will be very hard to recruit talents. Of course, good engineers can learn anything. Even though it's not always that simple. I read that sometimes new hires refused to learn Elm [4] because they wouldn't see the value for their curriculum!

Anyway, there is no magic rule of thumb here, but I would recommend to get the people part right because it matters more. Any technology in the hands of reasonable craftsmen will always perform better over time than great technologies under disastrous management.

Architecture Legacy

Centuries old tsunami stone in Japan, warning descendants to not build any homes below this point because of great tsunamis

In order to help future engineers understand your choices, and their context, a good practice consists in documenting architecturally significant decisions.

The idea is to answer potential Why? questions, and focus on «design decisions that are costly to change» [5] [6].

The documents must be relatively short to read, but must at least describe the context, what options were considered, with their pros and cons, and what are the consequences of the decision. And must of course be kept in the repo along with the source code.

Check out the various templates, and examples, think long term, and start writing architecture decision records!

Many thanks to everyone that participated in these extremely valuable conversations about this topic lately! And a special one to Benson who introduced me to the work of Stewart Brand.

Please share your feedback and ideas, and as usual don't hesitate to correct me if I'm wrong!

While I was writing this article, Justin wrote 20 Things I’ve Learned in my 20 Years as a Software Engineer and I think it's is a nice complementary read of this one :)

| [1] | https://medium.com/preply-engineering/do-you-want-to-be-right-or-successful-52a2cd0a220b |

| [2] | https://www.joelonsoftware.com/2000/04/06/things-you-should-never-do-part-i/ |

| [3] | http://conviviality.ouvaton.org/spip.php?article39 |

| [4] | https://discourse.elm-lang.org/t/reasons-that-people-were-forced-to-move-from-elm-to-something-else/6390/18 |

| [5] | https://medium.com/olzzio/from-architectural-decisions-to-design-decisions-f05f6d57032b |

| [6] | https://cognitect.com/blog/2011/11/15/documenting-architecture-decisions |

#tips, #methodology - Posted in the Dev category